Featured

100 years of Old Man Gloom: Zozobra celebrates a century of spectacle

When moving to New Mexico in 1920, Will Shuster never imagined a legacy beyond his art.

Though a century later, his envisioned spectacle lives on.

Arriving in Santa Fe to heal from lung damage in World War I, Shuster immersed himself in the Santa Fe art scene. In 1921, he became a founding member of Los Cinco Pintores — which was Santa Fe’s first modern artists collective. The collective included Shuster, Fremont Ellis, Walter Mruk, Jozef Bakos, and Willard Nash.

The five worked together to “flip” the local art scene on its head by making it accessible to the community. This meant taking art outside of galleries and showcasing in community spaces such as schools and hospitals — even the New Mexico State Penitentiary.

By fall of 1924, the seed for Shuster’s most grand piece of art was ready to come to fruition.

With the help of others, Shuster helped develop the idea for Zozobra.

On Friday, a crowd of more than 60,000 is expected at Fort Marcy Park in Santa Fe to witness the fiery milestone moment for Zozobra. It also will be broadcast by KOAT TV beginning at 8 p.m.

“I’m in awe, to be quite honest,” said Ray Sandoval, Zozobra event chair. “The community support has been so strong and this year it’s coming together.”

Since 1964, the Kiwanis Club of Santa Fe has been responsible for continuing the historic tradition.

From 1924, until 1964, Shuster personally oversaw the construction of Zozobra.

Sandoval said the event — even in its centennial celebration — has still remained up to Shuster’s standards.

“Shuster would talk about this black sky and being able to paint on it,” Sandoval said. “He’s writing this down in his diary in 1929. Will Shuster was so far ahead of his time. He always said Zozobra was supposed to be a spectacle.”

Since the first burning, it has been.

The first Zozobra

Shuster created the first Zozobra in 1924 as the signature highlight of a private party. He was inspired by Easter Holy Week traditions in the Yaqui Indian communities of Arizona and Mexico, in which an effigy of Judas was led around the village on a donkey and ultimately set alight.

In an interview on July 30, 1964, with Sylvia Loomis for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Shuster said:

“We (Shuster and Dana Johnson, head of Santa Fe Fiesta Council) got together and hatched out this idea of making an Old Man Gloom and he dug up the name for it from a Spanish dictionary, which means the gloomy one.

“Dan Eastman, Max Eastman’s son, was here at the time and he helped me build this first one which was only about 18 feet high. I remember we stuffed it with excelsior which we had soaked in copper sulfate and then dried and stuffed it with that. The idea being that we’d get a beautiful blue green flame. Gus Baumann made the head out of a cardboard carton. Well, this carton was too small. It looked like a little pin head on top of this figure 18 feet high, after having done that first one, I realized if we were going to make a head it had to be a big head — the head is about 9 feet high now. Anyway, I had the Kiwanians who took the part of ‘glooms’ in a procession around the figure, carrying green torches and then we had a bunch of artists who were the merrymakers who came on with colored whips and whipped the glooms away and ignited the figure. All of our work with the copper sulfate just went up in one kind of a puff of blue-green flame and that was the end of it.”

Zozobra today

For the centennial celebration, Sandoval said there will be plenty of spectacle.

Sandoval said Santa Fe turned 400 years old in 2012. Eleven years ago, the Santa Fe Fiestas celebrated 300 years and the Santa Fe Indian Market marked its 100th year in 2023.

“For us, we are hitting a milestone and wanted everyone to know about the tradition behind the event and how we are moving it into the modern world,” Sandoval said “We really want to make sure people talk about this Zozobra burning for decades, all while pushing the envelope. We need to teach our kids that milestones are important and we need to celebrate them.”

State Historian Rob Martinez said the burning of Zozobra kicks off the annual Fiesta de Santa Fe.

“The Santa Fe Fiestas are both ancient and modern,” Martinez said. “The event is still evolving as Santa Fe wrestles to celebrate its diverse landscape. There’s underlying history that has to be reconciled.”

Sandoval said Shuster always wanted to take people on a journey through color and sound.

“For years, we’ve taken his foundation and brought it to the modern era,” Sandoval said. “Shuster would experiment with Zozobra, He felt like Zozobra had to be different each year and that’s what we did with The Zozobra Decades Project.”

Beginning in 2014 through 2023, the Kiwanis Club revisited Zozobra’s past through the 10-year journey through each successive decade of Zozobra’s existence.

Sandoval said the project focused on creating a comprehensive and cohesive design that blends the style and substance of each era in Zozobra’s life and demise.

Volunteers delved into Zozobra’s look throughout the previous years, matching the overall design of all the elements — from his face and attire to the artifacts and music — with the history and events of each era.

“This year, Zozobra will have a different look,” Sandoval said. “The black canvas will be decorated with color from the drone show that we are doing.”

Doing it right

In the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution interview, Shuster continued about designing Zozobra:

“Well, I have a model that I made at the armature — scale of an inch to the foot that we follow each year. So even though it varies in expression or appearance a bit, it is pretty much the same thing because of the foundation,” Shuster said. “During the war … there was one year we did it and made the head look like a combination of Hirohito, Hitler and Mussolini. We called him Hirohitlomus instead of Zozobra. But, the second year, the next year we couldn’t do it and we built a small figure about six feet high and burned him on the corner of the Plaza by the art museum and a group of us dressed as clowns with hoses to keep the fire under control, and then we’d hose each other and hose the spectators. Just playing clowns. For a couple years I didn’t do it. One year, Ceril K. Scott had an art class and they did it out on the lot at the Saint Michael’s field there. They just erected a pole and cut out a head from compo board, fastened it to the top of the pole and built a little ring of fire — wood around the bottom of the pole. After I saw that I knew I had to take it over again.”

Major undertaking

Sandoval and the members of the Kiwanis Club work for months in creating Zozobra.

As the event grows, so have the logistics.

“How do you get more than 60,000 people in the park and keep them all safe?” Sandoval asked. “That’s our biggest concern. Public safety is at the forefront so that the community as a whole can enjoy this New Mexico tradition.”

Scott Wiseman is one of the Kiwanis members who has worked on Zozobra for decades. Though his working relationship with Zozobra started when he was 11.

“That’s when I started stuffing Zozobra,” Wiseman said. “I’m 41 now, so it’s been 30 years of involvement.”

Since 2008, Wiseman began working on Zozobra’s hands.

For the 100th anniversary burning, Wiseman will be there again.

“When I was entrusted with that task, I knew I had to make it something special,” Wiseman said. “My background is in art and design and I knew I had to utilize my skill set. I’ve taken figure drawing classes and focused on hands. With that, there’s not a lot of forgiveness if you do something wrong.”

Wiseman says being part of Zozobra means community.

“It takes a village with many moving parts literally and figuratively,” Wiseman said. “Pretty much everybody is a volunteer except for professional services. The money the Kiwanis makes goes back to the community in the form of grants and scholarships.”

While it has taken a lot of work, Sandoval said it’s rewarding despite the criticism that has come along with Zozobra’s ever-changing looks.

“Will Shuster never had one Zozobra that looked the same,” Sandoval said. “We’re holding true to this tradition all while bringing the community together.”

When Sandoval was 18 years old, he was asked by Harold Gans to keep the tradition alive. Gans was known for being the voice of Zozobra for decades.

Looking back with less than a week before the centennial event, Sandoval thinks that Shuster would be satisfied with the continuing legacy.

“I think he would be blown away that we had children submit 600 pieces of art for the show,” Sandoval said. “Shuster always wanted Zozobra to reflect life. We have a lesson for the rest of the world that when we come together to burn our gloom, it makes a difference. We are that community that Shuster envisioned.”

Still burning: 'Zozobra: A Fire That Never Goes Out' explores 100 years of Old Man Gloom

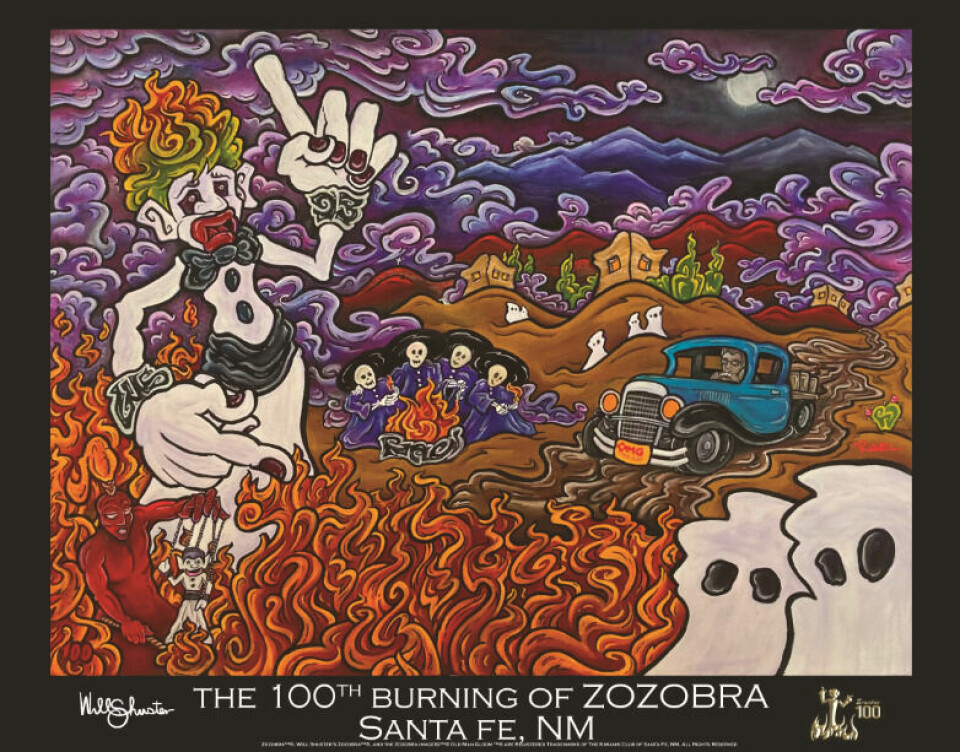

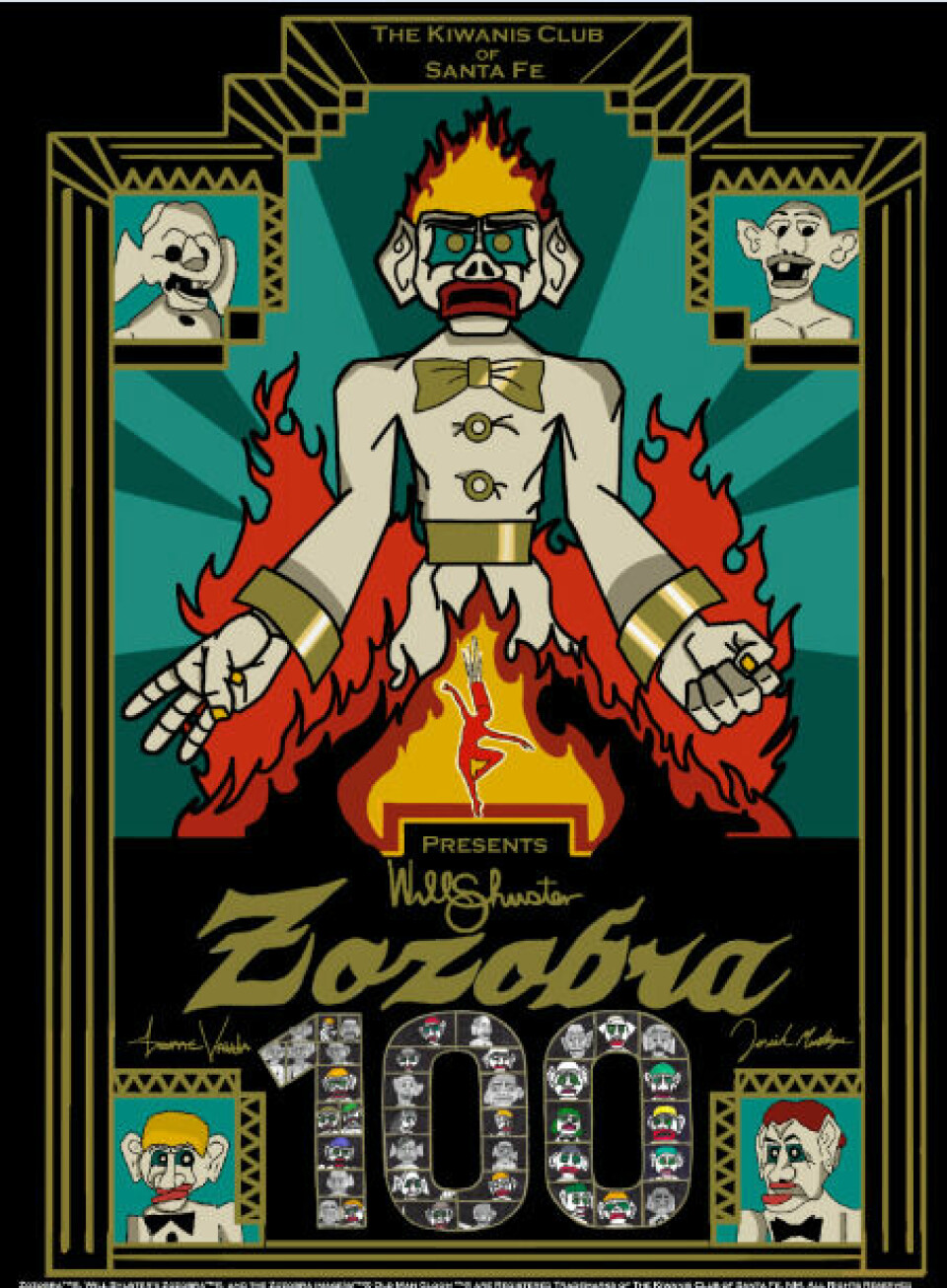

100 years of burning: 2024 Zozobra T-shirt, poster artists announced

20+ pictures of Zozobra through the years